I have to admit that I don’t live in Alberta anymore. After a 35-year work sojourn, my wife and I left for B.C.’s Sunshine Coast, returning to roots and escaping the prairie winters in our retirement.

I have to admit that I don’t live in Alberta anymore. After a 35-year work sojourn, my wife and I left for B.C.’s Sunshine Coast, returning to roots and escaping the prairie winters in our retirement.

Our adult children have also left, choosing to live in London and Vancouver rather than Calgary, their birth home.

Whenever I get the chance, I also talk to the children of our friends, now all in their 30s, about what they’re looking for in terms of employment, housing and quality of life. I haven’t spoken to one who thinks it’s all about reviving the oil and gas industry so Fort McMurray can become their home.

On the advice of one of my old Calgary pals (who now lives on one of B.C.’s Gulf Islands), I try not to be comparative in terms of the lives of our children and their peers, and our choices at their time of life.

So much is different now than in the late 1970s when we chucked Vancouver aside and made our way to Calgary, then just beginning its last great oil boom. We really decided to go there because my wife was accepted into the innovative new architecture program at the University of Calgary. I followed, fresh out of law school, open to new challenges.

In those days, no one was aware of the impending climate crisis. You could find a job within a month (if not weeks) of pounding the streets and new housing developments were eating up the prairie in all directions.

Almost everyone we met was from ‘away,’ having chosen Calgary because of its economic buzz, it’s friendly prairie spirit and the promise of a new future.

Prairie conservatism took its form from Peter Lougheed’s government (he was premier from 1971 to 1985). He was very much a Progressive Conservative, forward thinking and philosophically committed to social reform. Of course, he presided over a period of economic growth. But he also thought forward to when the oil boom would end and the next economy would take root.

The old Alberta guard, well represented by my first Calgary boss, Harold Millican, CEO of the Northern Pipeline Agency (and formerly Premier Lougheed’s chief of staff), fondly spoke of the province’s agricultural and ranching roots.

That old guard was mildly amused by the rise of oil and gas, which in their youth still had the reputation of being a somewhat dirty and crude way to make a living. It certainly didn’t define the Alberta economy the way it does now. And they didn’t assume it was forever. In fact, they expected it to end.

So bearing those older realities in mind, I wonder how Millican and Lougheed would view the current economic state of affairs, especially through the eyes of young Albertans?

First of all, they would think about new opportunities. They’d bemoan the lack of Heritage Savings Trust Fund investments in economic diversification, and they’d be travelling to and studying other jurisdictions, particularly in the U.S., where oil had ended and something else had begun.

I’m sure they would be encouraging Alberta’s universities and institutes of technology to promote research and instruction in new modes of production.

They wouldn’t be privatizing and shuttering provincial parks; they’d be encouraging back-country tourism and the muscle-driven outdoor pursuits of their youth.

They would also be studying the potential positive impacts of climate change on Alberta agriculture, and encouraging research into new crops and expanded boreal zone agricultural utilization.

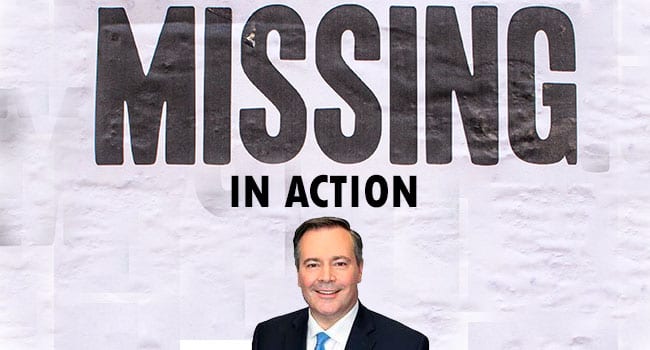

The great challenge facing Albertans right now is the lack of multi-generational political leadership that truly remembers what kind of options existed before oil and gas. Someone who can conceptualize that kind of multi-optioned future.

The province is stuck in a one-generational political rut that’s built on memories of easy money, no need for provincial sales taxes and a dependence on economic outsiders to do the inside thinking.

This isn’t a recipe for retaining bright young Albertans in the land of their birth. It’s also not very Albertan in its intellectual roots.

It’s really time to start channeling the inner progressive conservative Lougheed persona and start thinking in a more diverse political manner about the province’s future.

Mike Robinson has been CEO of three Canadian NGOs: the Arctic Institute of North America, the Glenbow Museum and the Bill Reid Gallery. Mike has chaired the national boards of Friends of the Earth, the David Suzuki Foundation, and the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society. In 2004, he became a Member of the Order of Canada.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.