Debunking the misconceptions about Canada’s first Prime Minister

McMaster University recently felt it necessary to apologize for its “grave oversight” of including “Sir John A. Macdonald Day” in its university calendar of events.

McMaster University recently felt it necessary to apologize for its “grave oversight” of including “Sir John A. Macdonald Day” in its university calendar of events.

Why? Because, according to McMaster, it is “a day that celebrates a person responsible for the genocide and oppression of Indigenous peoples in Canada.”

The National Post news story about the University’s apology added that Macdonald was also known for his part in the “development of the residential school system” and the Chinese Head Tax. However, both sources offer a wildly incomplete representation of Macdonald’s record, and a misunderstanding of actual Canadian history.

McMaster is not the only Canadian institution guilty of such ahistorical thinking. Queen’s University removed his name from Macdonald Hall, numerous statutes of Macdonald have disappeared from public view, and his name has been dropped from schools and public buildings across Canada. Often with little to no public input and certainly with no effort at a balanced review of the historical record.

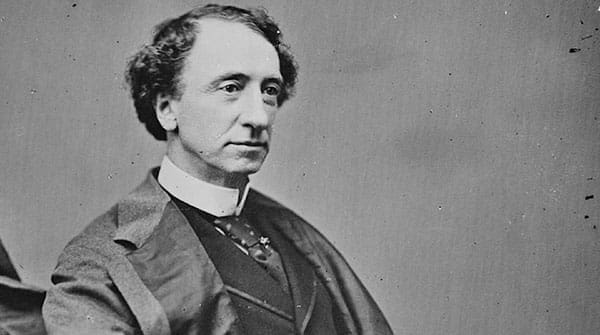

Sir John A. Macdonald |

| Related Stories |

| John A. Macdonald was a passionate advocate for Indigenous rights

|

| Sir John A. Macdonald: the enduring legacy of a great Canadian hero

|

| John A. Macdonald’s mistake

|

In fact, a review of his record shows that Sir John A. Macdonald can reasonably be credited with saving more Indigenous lives than any other Canadian prime minister.

His Conservative governments in both pre-Confederation Upper Canada and post-Confederation Canada ran decades-long programs to vaccinate all Indigenous Canadians, even in remote areas, against the deadly scourge of smallpox for which they had little resistance.

In the late 1870s, when the western buffalo population collapsed, a resource tens of thousands of Indigenous Canadians relied on for food and clothing, he immediately implemented what was almost certainly the largest famine relief program in Canadian history. It was a huge logistical effort given there was no railway across Canada. Food had to be shipped through the United States and then north to Canada by horse-drawn carts – a journey of months.

Each of these initiatives saved tens of thousands of Indigenous lives.

Macdonald also insisted on having treaties in place before allowing settlement of the vast expanse of western and Northern Canada acquired through the purchase of Rupert’s Land from Great Britain. And he created the Northwest Mounted Police to patrol the border against American settlers and liquor traders and to keep the peace in the new territory.

We can contrast Canada’s settlement experience with that of the U.S., where 60,000 or more Indigenous Americans (and 20,000 settlers and soldiers) lost their lives in Indian wars. In Canada, there were none.

As to residential schools, they existed in Canada long before Confederation and were voluntarily attended. Macdonald’s government did build 185 day schools and 20 residential schools largely in compliance with its obligations under the Western Treaties, but attendance was voluntary at both during his lifetime. A policy that continued for many years after his death.

The department of Indian Affairs delivered to Parliament each year a lengthy report summarizing its activities across the country including student attendance at the Indian schools.

The government paid the churches operating the residential schools a fee for each day a child was in school. One of the tasks of the local Indian agent was to inspect each school monthly, attend a roll call and ensure that every child was present. No child could simply disappear.

Many Canadians, understandably given media coverage, believe that most Indigenous children attended residential schools. However, this is untrue. The majority of Indigenous children who attended school (and many didn’t attend at all) went to a day school and walked home each night.

Of the minority of Indigenous students who attended residential schools, 50 percent dropped out after Grade 1 and almost none made it to Grade 5. This was true from the 1890s into the 1950s, by which point the government had begun closing the residential schools.

As to the Chinese Head Tax, an objectively distasteful policy, it was a response to the flood of Chinese workers who arrived on the West Coast following the discovery of gold – first in California and then in British Columbia. The workers were fleeing a decades-long civil war in China in which the death toll had reached 80 million at a time when Canada’s population was a mere four million.

One of the major complaints against the workers was that they had no interest in settling in Canada. They hoped to save enough after three or four years to live off the interest for the rest of their lives in China.

Macdonald was under tremendous pressure from British Columbia to discourage the flood of Chinese workers entering the province. Showing the political acumen for which he was famous, he first delayed the issue, arguing in Parliament that the workers were essential to the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR). Then, when the CPR was almost complete, and he could delay the issue no longer, he set up a commission, appointed known political allies as its members, and six months later received its recommendation for a $10 head tax. British Columbia had been seeking $100.

There was a political firestorm following the release of the committee’s report, and Macdonald ultimately settled for a $50 head tax. However, the head tax had little impact on Chinese immigration, which recovered within five years to its pre-head tax levels.

Fifteen years later, it was the government of Liberal Prime Minister Sir Wilfred Laurier which doubled the head tax to $100. Followed by a commission stocked with his political allies that two years later recommended a $500 head tax Laurier then implemented.

By all means, Canadians should reflect on the lessons to be learned from their history – the good and the bad – the problems their ancestors confronted and the political and practical limitations on what was possible.

But doing so requires examining the actual historical record rather than relying solely on current media narratives influenced heavily by the agenda of the government of the day.

Greg Piasetzki is a Senior Fellow at the Aristotle Foundation, chapter author for The 1867 Project, a Toronto lawyer and a citizen of the Metis Nation of Ontario.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.