What is the ’60s Scoop and why should a conversation about it still matter to Canadians today?

What is the ’60s Scoop and why should a conversation about it still matter to Canadians today?

The ’60s Scoop has been much in the news recently, and I expect we’ll hear much more about it in the coming weeks and years.

I’m guessing there are already plans to make it the subject of the next major inquiry, soon after the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls has wrapped up.

It’s usually described as a decade when Indigenous children were stolen from their parents by overzealous social workers attempting to perpetuate cultural genocide by placing these children in the homes of non-Indigenous Canadians and Americans.

It’s true that some child welfare workers, who were seeing the appalling conditions on reserves for the first time, were probably overzealous in removing children from what they saw as unsafe homes and inadequate care.

It’s also true that adopting these children into non-Indigenous homes was a bad idea. The adoptions caused other problems at an alarming rate for cultural reasons and the fact – now recognized – that many of these children suffered fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD), having been born with damaged brains as a result of exposure to alcohol in the womb.

The adoption of Indigenous children into the homes of other people has been discontinued.

But the practice of removing far too many Indigenous children from their parents hasn’t changed much from the 1960s to the present, even with the devolution of child welfare responsibility to Indigenous agencies. In fact, Manitoba now has more Indigenous children in care than during the 1960s.

So except for the international adoption aspect, the child welfare situation in Manitoba is virtually the same as during the ’60s Scoop.

Why are so many Indigenous children taken into care each year? Why are even more left in bad homes with poor care? And why are so many of these children born with FASD?

The answer is that the parents of these children abuse alcohol. They drink to the point where they’re incapable of being responsible parents.

And how could Manitoba’s child welfare crisis and Manitoba’s horrendous FASD problem be brought under control?

Irresponsible parents would have to stop drinking.

Many will consider this observation callous and even ignorant. They will want to point to colonialism, residential schools and other historical facts they think to explain that alcohol abuse in Indigenous communities is inevitable.

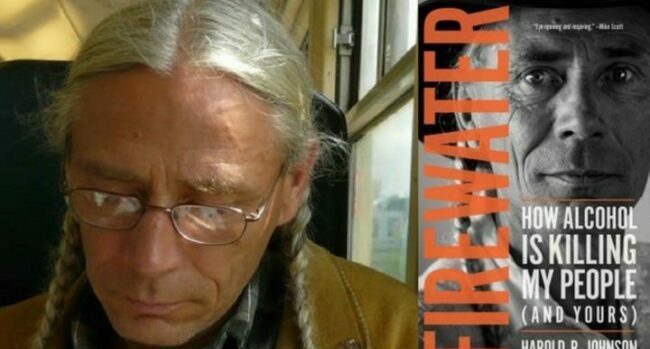

Harold Johnson disagrees. In an important new book Firewater: How Alcohol is Killing My People (and Yours), he takes direct aim at what he calls the “Victim Model.” He insists that the enormous problem of alcohol abuse that plagues so many Indigenous communities must be acknowledged and openly discussed if there is to be any hope of change. He doesn’t deny that the historical injustices are real, but he passionately believes that using them as an excuse condemns Indigenous people to be helpless victims forever.

He asks why Indigenous leaders, who are so vocal on some issues, seem so afraid of acknowledging the problem. He points with some humour to the 1996 Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples that devoted a measly few pages of its massive $60-million report to rampant alcohol abuse in the Indigenous community. He concludes – farcically – that it was seen as being no particular problem.

He wonders if the leaders fear that someone will raise the old “drunken Indian” stereotype if the issue is openly and honestly discussed. So they remain silent.

He also wonders why non-Indigenous people in important positions are so strangely silent on a problem that’s so obvious. He says, correctly, that white people who use the words “Indian” and “alcohol” in the same sentence will find themselves branded as racist. Johnson says these people too must gather their courage and speak out.

And just who is Harold R. Johnson to say these things? He’s a Cree from Treaty Six Territory in Saskatchewan.

Johnson had a hard life. His father died young, as did his siblings. He was bitter and lived a life of hard drinking as a young man. But then he did a major rethink. He went back to school, became a lawyer and a Harvard graduate. He quit drinking completely and has been a respected Crown prosecutor in Saskatchewan for years.

Johnson turned his life around not as a result of anything a government did or did not do. He did so as a person deciding how he wanted to live his life. He explains that he never saw himself as a victim but as a person responsible for his own future.

“I can’t stay silent any longer,” he writes. “I cannot with good conscience bury another relative. I have now buried two brothers who were killed by drunk drivers. I cannot watch any longer as a constant stream of our relatives come into the justice system because of the horrible things they did to each other while they were drunk. The suffering caused by alcohol, the kids with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD), the violence, the poverty, the abandoned children, the mental wards and the emergency rooms, the injuries and the illnesses and the loss of hope and the suicides have all piled up within me to the point that I must speak.”

And speak he does. He estimates that 50 per cent of people in Treaty Six communities die directly or indirectly from alcohol. He notes that in many Indigenous communities, alcohol and its aftermath are the only real economy. He refers to the judges, lawyers and workers who hold court in these communities, where virtually all the cases involve drunken misbehaviour, as “Alcohol Aftermath Administrators.” They do their work, only to come back and find the same people in front of them again and again. Despite their best efforts, they accomplish little.

Johnson says we all live by the stories we tell ourselves. But sometimes we’re fooling ourselves. Here are some of the stories that occur to me:

The story told about the ’60s Scoop is of uncaring social workers stealing children from their parents and hurting them both. But the real story is about irresponsible parents abusing alcohol and placing their children in danger. The real story is about drinking.

The story about the child welfare system is of a government and a system that doesn’t know what to do with the thousands of Indigenous children who come into care. That part of the story is true but the real story is about drinking.

The story told about the justice system is of racism and too many Indigenous people going to jail. The real story is about drinking.

The story told about missing women is about Indigenous women being treated as less than human, and too often casually murdered and forgotten. That part of the story is true, but the real story is about women driven from their communities by alcohol-fuelled violence, and the many more Indigenous women with no option but to stay behind, trapped in hopelessness.

The story is told of communities with epidemics of young people who see suicide as the only option, the Indigenous leaders who demand that the government fix the problem. And the government responds with money and programs that both the leaders and the government know will make no difference. The real story is of young people driven to despair by their parents’ drinking.

The story about FASD is about how it affects all races and groups (true) and that there is not a grossly disproportionate number of Indigenous FASD children in Manitoba, for example (untrue). The real story is about irresponsible parents drinking.

Johnson, however, offers some hope. He notes that, according to his research, 35 per cent of Indigenous people don’t drink at all. That’s higher than the figure for non-Indigenous non-drinkers. These people can lead the way. He talks of “sober houses,” based on the Block Parent model, where people returning from jails and treatment centres with the motivation to change could drop in and have a cup of tea and a chat, instead of immediately being thrust back into a community where even their friends and family are urging them to have a drink.

He talks about motivated communities turning themselves into virtual treatment centres. Everyone in such a community would have to be fully committed to the plan, as opposed to “dry reserves” where the bootleggers are often middle-class people who have the money to buy pickup trucks and pay the bribes necessary to operate.

None of these solutions have anything to do with government programs, government money or national inquiries. Instead, they involve individuals making personal decisions to stop thinking of themselves as victims and then making positive changes to stop drinking.

Finally, Johnson notes that maybe the elders knew best all along. When Treaty Six was negotiated, the one thing Indigenous negotiators were adamant about was that there must be an absolute ban on alcohol in the treaty area (this was later struck down in the Drybones case by the white elders of the Supreme Court of Canada who thought they knew better).

Harold Johnson didn’t have to write this book. He knew he would be criticized by many for doing so. He felt a duty to tell a story that needs to be told.

All Canadians should read it to understand what happened during the ’60s Scoop and what’s happening today.

Brian Giesbrecht is a retired Manitoba judge and a senior fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

Brian is a Troy Media Thought Leader. Why aren’t you?

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.