Trudeau’s genocide narrative undermined by Mark Bourrie’s book, Bush Runner

It has been two years since the Prime Minister of Canada told the world his nation is a genocidal state and hinted that indigenous children were murdered by priests and others in residential schools. His take was soon the accepted global response to the presence of cemeteries with unmarked graves in western Canada.

It has been two years since the Prime Minister of Canada told the world his nation is a genocidal state and hinted that indigenous children were murdered by priests and others in residential schools. His take was soon the accepted global response to the presence of cemeteries with unmarked graves in western Canada.

This followed the deluge of stories emerging from public hearings into the schools, many heart-wrenching. The Prime Minister then did an obsequious photo op with a teddy bear in a cemetery that holds the bodies of Rez children and others in the community. He certainly didn’t know who was there.

In the furore provoked by Trudeau’s grandstanding, Canada’s first Prime Minister, the founder of a downtown Toronto university, several former premiers and governors-general and a host of educators and business people were made non-persons by Social Justice Warrior acolytes applying their standards to the history of the 1870s. You’d be forgiven for thinking it was time someone seriously investigated the charges of murder and torture.

|

| Related Stories |

| John A Macdonald was a passionate advocate for Indigenous rights

|

| Erase our history, erase ourselves

|

| Rethinking the history of the Lakota of the Great Plains

|

But no. In the two years since Trudeau waded into waters polluted by his father Pierre’s white paper in the 1960s, not a single body has been exhumed, not a single grave has been investigated, not a single allegation of murder has been even reasonably put to the test. Yes, hundreds of children died over the century-plus the schools existed – mostly dying of the same diseases afflicting children of that age. But proof of worse is not forthcoming.

In several cases, Trudeau was told by chiefs that the locals knew precisely who was buried in those graves, including non-indigenous persons. Trudeau was unrepentant. It was Teddy bear or bust.

The ghosts of Trudeau’s agitation thrive on the ignorance and political expedience of self-loathing Canadians, many of whom have a faint grasp of history beyond the last media cycle. Academics sipped long and deep into the most outrageous unproven accusations. The current school curriculum is certainly uninterested in anything but an #ESG crayon version of the nation’s history. The artistic community has obsessed about unproven claims without offering any proof.

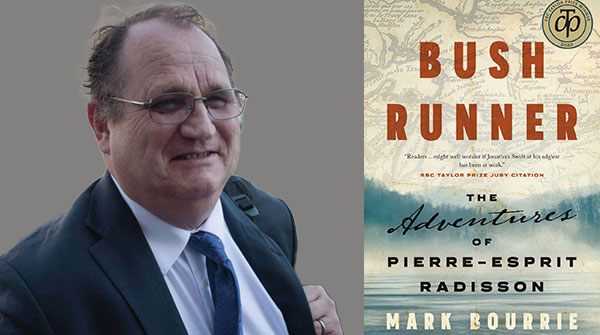

Which is why Bush Runner, Mark Bourrie’s 2019 clear-eyed history of Pierre-Esprit Radisson, the 17th-century adventurer/entrepreneur and founder, in part, of the Hudson’s Bay Company, should be required reading for all Canadians with a flawed interpretation of the country’s origins. That includes Trudeau. Using Radisson’s own journals of his travels around the Great Lakes and further West (which miraculously survived to be published 200 years later), Bourrie paints a picture of a continent roiled by wars between Iroquois and Hurons and the after-effects of smallpox plagues that killed up to half of the population.

The through-line in this vivid history is the arrival of 15-year-old Radisson and other French settlers in the early to mid-17th century. (The natives thought them short and ugly with their pox-riddled skin.) Radisson was not a colonizer; he was a salty trader looking to get rich off the beaver trade. He was soon captured by Iroquois.

Using Radisson’s own detailed notes, Bourrie describes a clash of cultures Radisson saw in what was called a wooded virgin paradise after the loss of so many natives to disease. Bourrie deftly portrays the ever-changing alliances and rivalries Radisson discovered amidst the tribes when he was captured and then adopted by a wealthy Iroquois family.

A gregarious huckster, Radisson ingratiated himself into the culture, quickly learning the language and customs. Bourrie makes no attempt to sugarcoat the dangers of life in the woods, the cruelty of natives to each other and white settlers. He doesn’t hide Radisson’s history of cannibalism. But he also describes the advanced culture, the laws, the agriculture and the heroism of the society. And the pitiful French, English and Dutch stragglers pushing the boundaries west.

The people that Radisson is adopted by – and then betrays – are not figures of pity in Bourrie’s telling. In the face of encroaching destruction, they forgave Radisson’s treachery, allowing him a second chance after he tries to reunite with Europeans eager to buy his beaver pelts. Using his friendship with the tribes with whom he does business, he is soon being taken through the secret rivers and lake passages of the northeast and Great Lakes basin up to Hudson’s Bay.

He is tortured, fawned over and respected for his guile and survival instincts. Even as many die around him, Radisson learns to endure the long, cruel winters and, when break-up comes, to navigate the thousands of rivers, streams and lakes that cover the maps even today. He becomes the conduit for European explorers needing the penetrate the frozen continent.

In his search for wealth and position, Radisson eventually pops up in the courts of the English and French kings, beguiling them with his wild tales of life among the “savages” and with his written journals that end up in the hands of Kings Charles II and James II. Using fluid loyalties between the French and British he and his partner Medard des Groselliers launch a series of (often futile) attempts to exploit the beaver trade in first the Great Lakes and later Hudson’s Bay.

His ability to deal with the indigenous tribes allows him to become the conduit for the original HBC investors. But as the Europeans and then the indigenous have less use of his services, he becomes a sad figure, hoping for one final big score. By the time he dies at age 74 in London, the French have abandoned Quebec and most of the Mississippi, the Dutch have sold their American holdings to the British, and the Spanish remain in the south of the continent.

The template of ignorance that Trudeau and his father exploited has exacted a price. Bitter failures. Notable success in saving the Indigenous in Canada from the American fate. For those who get their Canadian history from the current CBC grievance culture, Bush Runner’s even-handed adventure story will shock with enough twists and turns to keep even the best screenwriter occupied.

It reinforces the impossibility of changing the past. But it also offers the promise of a better future if Canadians understand how far they can go if they embrace the true history of this wild land.

Bruce Dowbiggin is the editor of Not The Public Broadcaster. A two-time winner of the Gemini Award as Canada’s top television sports broadcaster, he’s a regular contributor to Sirius XM Canada Talks Ch. 167. Inexact Science: The Six Most Compelling Draft Years In NHL History, his new book with his son Evan, was voted the eighth best professional hockey book by bookauthority.org. His 2004 book Money Players was voted seventh best.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.