The stigma attached to being a Covid long-hauler has the potential to negatively impact patient outcomes

High levels of stigma experienced by some COVID long-haulers are associated with more intense symptoms, reduced physical function and loss of employment due to disability, according to newly published research from a Lancet medical journal.

Specialists working in Edmonton’s Long COVID Clinic began hearing patient stories suggestive of stigma as soon as the clinic became operational in June 2020. To explore this observation in a more systematic way, they developed a questionnaire designed to quantify the stigma being reported. They compared scores on the stigma questionnaire to other measures of health and well-being.

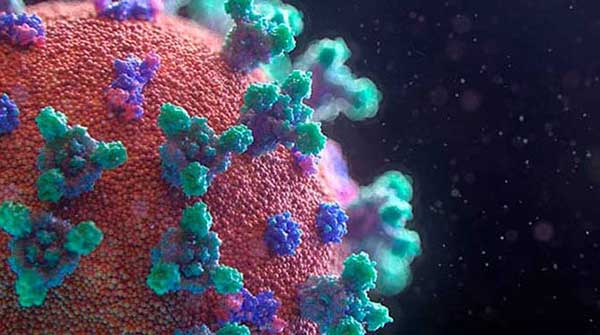

Long COVID, now officially labelled Post COVID-19 Condition by the World Health Organization, is characterized by non-infectious symptoms such as fatigue, cough, shortness of breath, brain fog, joint pain, headaches, diarrhea or rashes that persist for longer than three months following acute infection with SARS-CoV-2.

Ron Damant |

Daisy Fung |

|

| Related Stories |

| We drastically overreacted to the COVID-19 pandemic

|

| Is Omicron the beginning of the end of COVID-19?

|

| What parents need to know about the COVID-19 vaccine for kids

|

“We found that people with higher levels of stigma had more symptoms, lower function, reduced quality of life, and a greater chance of unemployment due to disability,” says Ron Damant, professor in the University of Alberta Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry.

“That’s not cause and effect, but it’s certainly a constellation of associations that are all pointing in the same direction – stigma among long COVID patients is real, and this stigma has the potential to negatively impact patient outcomes.”

Statistics Canada reports that nearly 15 per cent of Canadians, or 1.4 million people so far, report long COVID symptoms. They include stigma study participant Daisy Fung, family medicine physician and U of A assistant clinical professor.

Fung caught acute COVID in March 2020 and is still experiencing extreme post-exertional fatigue and muscle pain, and has been diagnosed with post-COVID myalgic encephalomyelitis, characterized by chronic fatigue. Also a mother of four and a community volunteer, Fung has had to cut back on her work hours, reduce teaching responsibilities, drop volunteer activities and avoid physical activity that worsens her symptoms.

Fung went public with her experiences of stigmatization – even from other medical professionals – in both social and traditional media.

“I’ve had lots of comments asking, ‘Why do predominantly women get this? Or only ‘well-to-do’ women?’ which are very inaccurate statements,” says Fung. “It felt accusatory, that it’s mental health or malingering or burnout, lots of things that are not true.”

Damant noted that stigma is considered a social determinant of health, a non-medical factor much like poverty, lack of educational opportunities or food insecurity that can have a major impact on physical well-being. His team’s approach to measuring stigma is modelled on similar tools for HIV, AIDS, epilepsy and leprosy.

The long COVID stigma survey was completed by 145 patients, and results were cross-referenced with information from their medical records, such as six-minute walking distance, clinical frailty score, and the number of other illnesses and emergency department visits.

Patients who experienced stigma were found in all demographic categories, but average scores were higher for women, Caucasians and people with lower educational opportunities. The overall average stigma score was 103 out of 200, or approximately four out of 10, where zero out of 10 represents no stigma and 10 out of 10 is severe stigma.

Patients with higher stigma scores were found to have a higher likelihood of more severe symptoms, anxiety, depression, reduced self-esteem and thoughts of self-harm, and were more likely to be unemployed due to disability.

“People said they were not allowed to return to work, ostracized from friends and family, subjected to unnecessary and humiliating infection control measures, accused of being lazy or weak, or accused of faking symptoms,” reports Damant.

While Damant acknowledges the sample size for the study was relatively small, he says the results are significant because it is one of the first quantitative examinations of stigma in long COVID patients. He hopes to refine the questionnaire and test it in other countries.

Damant also hopes attitudes will change as more is understood about long COVID and the impact of stigma on patients.

“I’m hopeful that, through increased health literacy and awareness, people will become more empathetic and open-minded,” he says.

Damant prescribes non-judgmental listening as the first step toward treating patients who experience stigma.

“People who are suffering from long COVID are not faking it; they’re not weak; they don’t need to be treated like they’ve got an infectious disease,” Damant says. “The misinformation, the stereotyping, the labelling, just perpetuate stigmatization, so we need to challenge that.”

Fung agrees. She says she even found comfort in the study results, realizing that her experience with disease-related stigma was not unique. Being a long COVID patient has helped her build empathy and made her more aware of everyone’s inherent biases.

“It’s been a struggle, a learning curve, that’s helped me start to advocate for other patients who may have chronic illness, including long COVID and especially myalgic encephalomyelitis, who have been ignored for decades, and I hope that they will benefit,” she says. “Kindness can help mitigate the harm.”

| By Gillian Rutherford

Gillian Rutherford is a reporter with the University of Alberta’s Folio online magazine. The University of Alberta is a Troy Media Editorial Content Provider Partner.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.