As we get off the bus at Sapa, Vietnam, my wife and I are enthusiastically greeted by the lilting voices of a group of women trying to sell us goods.

As we get off the bus at Sapa, Vietnam, my wife and I are enthusiastically greeted by the lilting voices of a group of women trying to sell us goods.

The sound floats through the crisp morning air of the Hoang Lien Son Mountain Range, where this city of 40,000 people is situated.

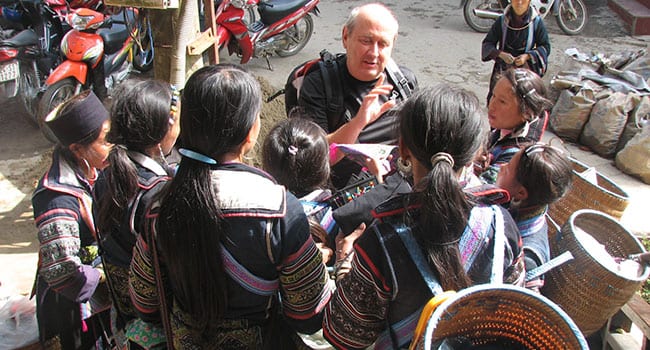

The women are dressed in embroidered denim and sparkling silver jewelry. Their hands are blue from the indigo dyes they use to make their clothing. Their fingers are calloused and cut from their sewing needles.

Their cheery smiles and hopeful words don’t reveal the difficult lives they live. They walk for an hour every day to greet prospective buyers – hoping to sell a trinket for enough to buy food for another day.

Meeting the diminutive women of the local hill tribes is unforgettable and enthralling. They seem ageless, with twinkling eyes and pleasing demeanours. Surprisingly, what seems to be a young girl turns out be a 50-year-old matron.

They throng around us to offer beautiful hand embroidery at bargain prices. A lovely purse costs a little more than $1.

Vietnamese legend tells the story of the lowland Dragon King marrying Au Co, a northern highland fairy. She laid 100 eggs, which hatched to become 100 sons. Eventually, the king became homesick and left with half his sons. The remainder, the Montagnards, became the 50 hill tribes of today.

Identified primarily by their clothing, headgear and jewelry, each tribe has distinct cultures and traditions. Black lacquered teeth, the use of platers (a long bamboo stick used to carry heavy loads), head scarves of varying colours and ornately-embroidered patterns hint at their origins.

We encounter many Hmong and Dzao women, but few men. The women explain that most men work the fields every day from dawn to dusk. The old folk watch the kids. Everyone contributes to feeding the family.

As we stroll to the local market (a must see), an old woman catches our eye – she sits quietly and alone, wearing the traditional red headdress of the Hmong. She’s sewing something that we strain to see.

On our approach, she looks up, ever hopeful. We see, in her gnarled hands, a perfect tiny hat. Its borders and edge are embroidered in reds, pinks and blues. It’s a perfect gift for a friend’s new baby.

The market is a sprawling affair. Every available space is cluttered with wares. Although visitors throng here and are welcomed, the market is for the locals.

We’re instantly drawn into the culture as we enter the market and listen to the bartering and bustle.

The smells are appealing and disturbing at the same time. We try to identify, by sight and smell, what they offer. First the easy stuff: birds’ eggs, fruits, vegetables, fish and prawns. But then we see a cow’s leg, a cage with cute puppies in it, insects that squirm in a large bowl, chicken heads and feet, a bucket of entrails and other things we don’t want to know!

From the many small villages that surround Sapa, the women walk each morning. We’re drawn to these villages and their mystical names: Cat Cat, Ban Ho, Ta Phin.

To arrive at our home stay, we walk the trails the water buffalo use, chickens darting out of our way, pot-bellied pigs wallowing in the paddies and tired looking men working the rice.

For a day, we live with a local family, sleep in their house and eat their food. They’re hospitable and friendly, sharing their meal and offering a sip of homemade rice wine.

Nestled along the Muong Hoa River, the homes are simple structures, made of thatch and wood. A mattress on the floor in one corner, a cooking pit in another and a sitting area with tiny wooden chairs at the centre of the home. Livestock roam freely through the yard and sometimes the house!

The stay with the family is enjoyable and fulfilling.

Some of the memories of this satisfying journey may fade with time but the sound of the lilting voices of the hill women will linger.

Part of every trip I take is to learn about and appreciate local flora and fauna. What I learned on this journey is that intense subsistence farming and hunting depletes local resources rapidly and almost completely.

We saw very few birds and no wild mammals. Parkland was almost non-existent and forest patches were tiny and disjointed. Even the fish – we took a water expedition one day – were minuscule, yet were caught for food. The market showcased these tiny fingerlings that should have been the hope for the future but were today’s food.

Not all of Vietnam is devoid of wildlife, but the areas where you see variety and numbers are limited and isolated.

Geoff Carpentier is a published author, expedition guide and environmental consultant. Visit Geoff online at www.avocetnatureservices.com, on LinkedIn and on Facebook.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.