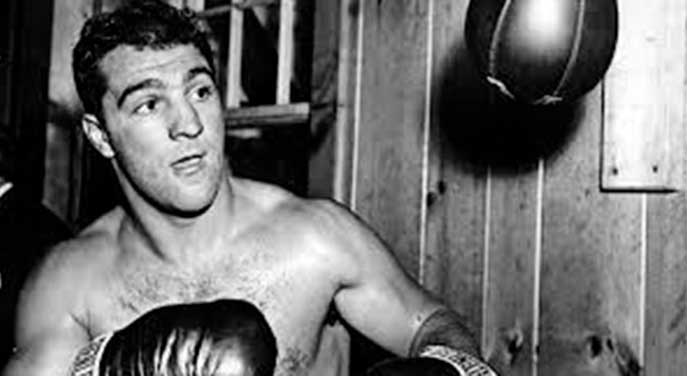

Being heavyweight champion of the world was a big deal when professional boxing was a mainstream sport – a very big deal. And in the early 1950s, an Italian-American called Rocky Marciano was the guy.

Being heavyweight champion of the world was a big deal when professional boxing was a mainstream sport – a very big deal. And in the early 1950s, an Italian-American called Rocky Marciano was the guy.

Born Rocco Marchegiano on Sept. 1, 1923, he was one of six children in a working-class Italian immigrant family – his father came from Abruzzo and his mother from Campania. Money was tight, which was something he never forgot. Avoiding poverty became an obsession.

Rocky came to boxing relatively late. He’d wanted to be a professional baseball player but didn’t make the grade. So in June 1948, he showed up in New York to audition for famous boxing trainer Charley Goldman.

Rocky wasn’t what you’d call a classy natural. He was all about brute force, relentless aggression, destructive punching power and a non-fastidious attitude toward the rules. The English sports journalist Peter Wilson described his approach as “legalized cobblestone brawling.” And noting his swarming style, someone else said that “fighting Marciano was like scuffling with an angry janitor inside a broom closet.”

Goldman’s early impression was that of a diamond in the rough. Rocky swung wildly, had no footwork, no balance and no defence. But he had power and the right attitude. With a lot of work, he could be taught enough basics to make him potentially formidable.

Even back then, Rocky was on the small side for a heavyweight champion. Shy of six feet in height and weighing 185 to 190 pounds, his arms were several inches shorter than those of illustrious predecessors like Joe Louis and Jack Dempsey. Meeting him in the flesh, President Dwight Eisenhower remarked that he was smaller than anticipated.

Rocky won the title in Philadelphia in September 1952. It was his 43rd fight and a come-from-behind victory that only a late knockout could rescue. Redemption arrived in the 13th round.

Rocky won the title in Philadelphia in September 1952. It was his 43rd fight and a come-from-behind victory that only a late knockout could rescue. Redemption arrived in the 13th round.

Three years later, his last fight was in New York’s Yankee Stadium on Sept. 21, 1955. More than 61,000 paying customers went through the turnstiles and another 100,000 or so showed up at theatres to watch on the new-fangled medium of closed-circuit television. They got their money’s worth.

Rocky’s opponent, Archie Moore, was a veteran of indeterminate age, a flamboyant showman and a shameless self-promoter. He could also fight, being highly skilled, a master of evasion and possessed of decent power. He would, he said, not only beat Rocky but knock him out.

And for a brief moment in the second round, this self-belief seemed plausible. Courtesy of a right-hand delivered with “classic brevity and conciseness,” Moore dumped Rocky on the floor for only the second time in his career. But Rocky promptly got up at the count of two, weathered the ensuing storm and eventually ended proceedings in the ninth. Along the way, it was what my local paper dubbed “a whale of a fight.”

Moore had this to say about his Marciano experience: “Rocky didn’t know enough boxing to know what a feint was. He never tried to outguess you. He just kept trying to knock your brains about. If he missed you with one punch, he just threw another.”

Finally, Rocky called time on his career, bowing out undefeated with a 49-0 record.

Maybe the relentless grind of the training camp and the punishing nature of his fights ultimately wore him down. Perhaps, pushing 33, he could sense the potential for slippage within himself. Or, as some suggested at the time, it might have been a quarrel over money with his manager.

Whatever the reason, he quit at the top. And he never tarnished his perfect record by trying a comeback.

He was, however, seriously tempted once. When the Swede Ingemar Johansson shocked the world by winning the title in 1959, Rocky considered a comeback, even going so far as secretly spending a month in training camp. But he dropped the idea.

In his heyday, Rocky was portrayed as a role model for the 1950s American male: achieving immigrant son, patriotic Second World War soldier, devoted family man, stoic in times of difficulty.

As is often the case, the reality was more complicated.

He actually spent 22 months in a U.S. Army prison for his wartime role in a robbery/assault and his commanding officer deemed him to be of “no value to the Army.” In private life, his social circle included notorious Mafia figures like Frankie Carbo and Vito Genovese.

Still, there’s no denying that he won the title fair and square, defended it against all comers and went out undefeated.

Not a bad epitaph for a champion.

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps a little bit. For interview requests, click here.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the authors’ alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.